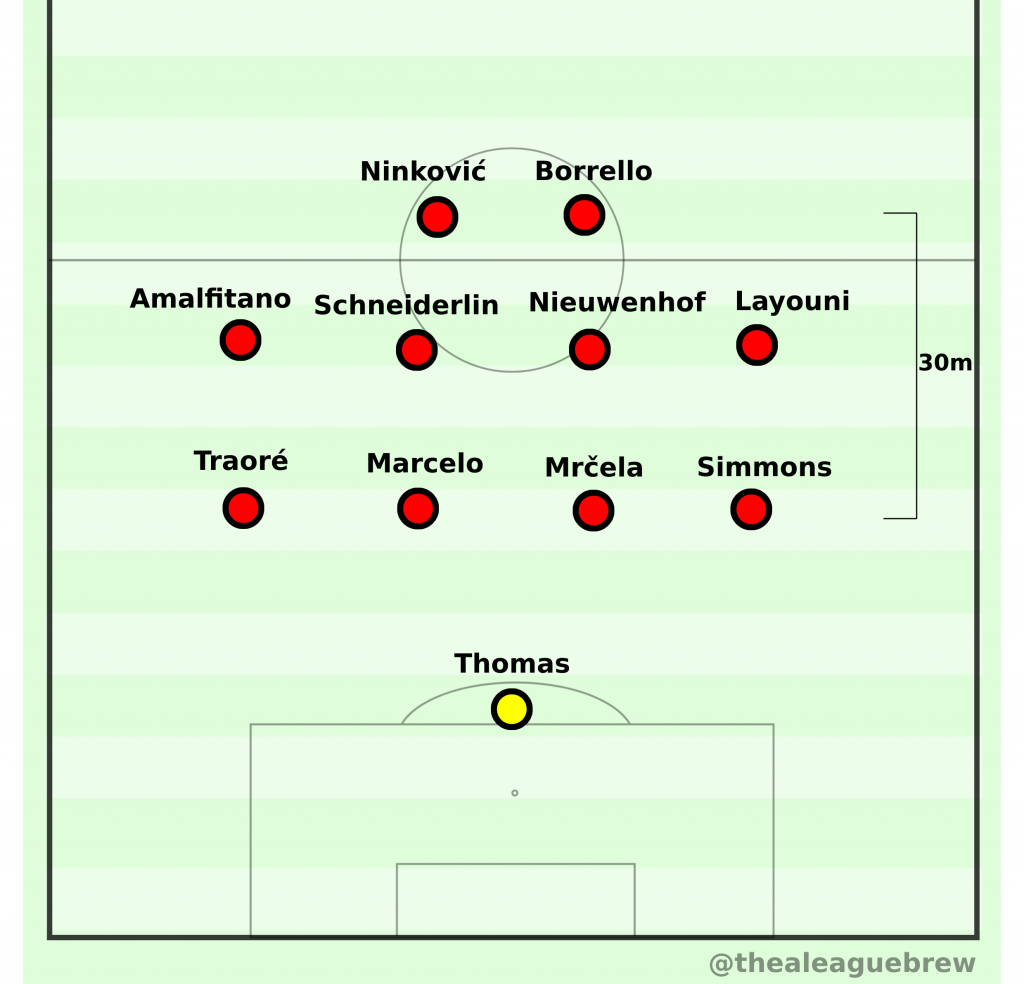

The Western Sydney Wanderers achieved the best defensive record in the A-League Men’s competition this season, having done so defending mostly in a compact, medium-block, 4-4-2 shape. This system is synonymous with a passive and rigid defensive style, aimed at absorbing pressure against superior opponents. Contrarily, Marko Rudan’s side displayed an active and fluid pressing style to control the middle-third, force turnovers, and profit from transition moments. This article will further analyse Rudan’s 4-4-2 medium-block, and how this style of defence was in many ways their best form of attack.

Rudan Controls the Middle-Third with Fluid Medium-Block

As their opponents constructed positional attacks in the middle-third, the Wanderers’ primary defensive objective was to control the centre of the pitch, and then subsequently force turnovers. Rudan developed a team that was fluid in their ability to achieve this, with a variety of pressing patterns arising throughout any given match, depending on the qualities of the opposition and their rotational movements.

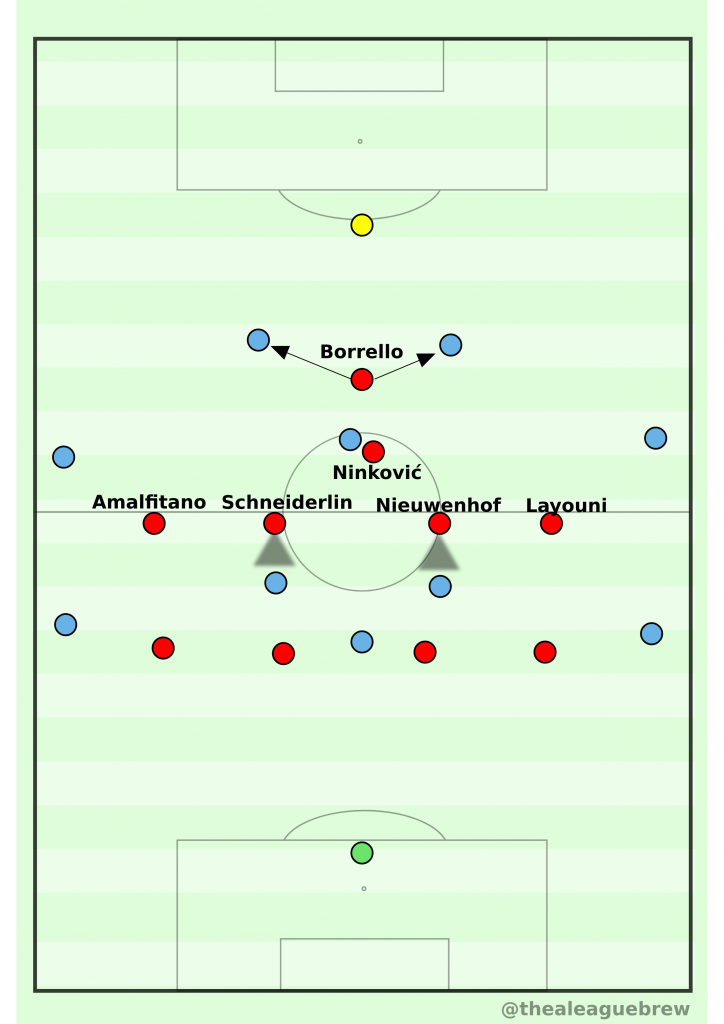

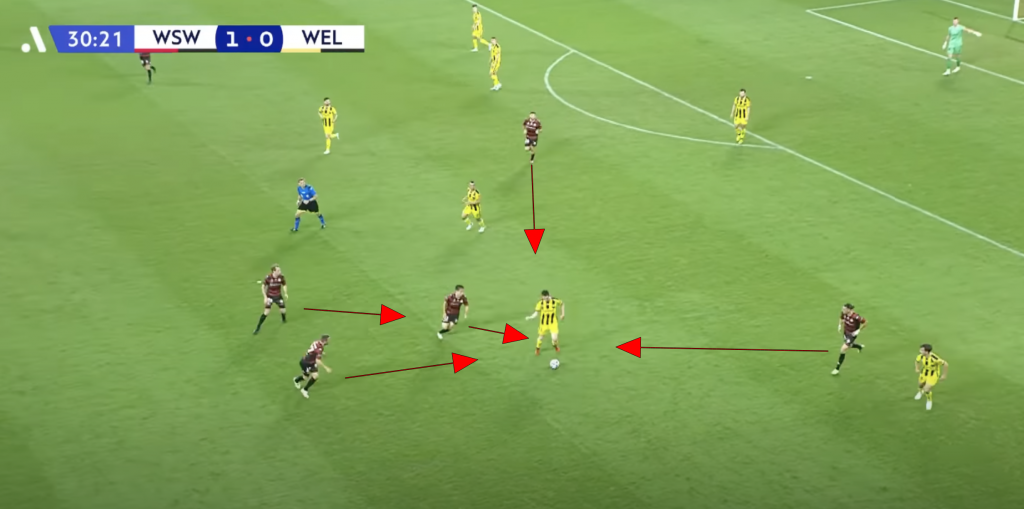

In a 4-4-2, the first step to dominating the centre is through the movement of the attacking pair. It was the responsibility of Borrello and Ninkovic to simultaneously apply pressure to the ball-carrying CB and block passing lanes through the central pivot. They could achieve this relatively easily against a 2-chain CB pair and a single pivot, or against poor ball-circulation, by using Borrello’s exceptional work-rate to press both CBs while Ninkovic statically man-marked the pivot (Diagram 2a), or by pressing the CB’s in tandem utilising cover shadows to cut off the pivot (Diagram 2b).

As the opponent increased the quality of ball-circulation, or added multiple pivots, or overloaded the backline with chains of 3 or 4 in build-up, solving pressing opportunities became more complex, and defensive fluidity was essential to the Wanderers’ success at applying pressure from the medium-block.

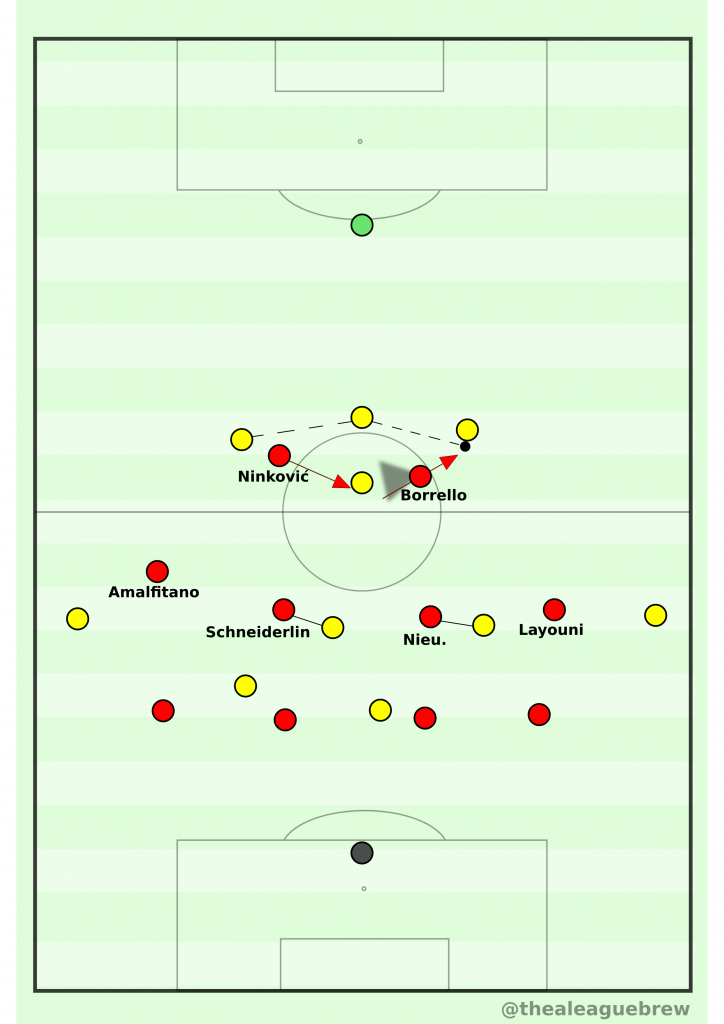

Fluidity means that roles and positions are not fixed. Players have the freedom to vacate their original position to affect the game. Rudan utilised defensive jumps to achieve fluidity. These “jumps” are pressing moments in which a player vacates their original position in their current defensive line, to apply pressure to opponents in a higher defensive line. Any of the 4 Wanderers midfield players were given the capacity to jump forward to support the attacking pair in applying pressure, meaning the Wanderers had a number of creative ways to solve overloads in the opponents’ build-up. Rather than instilling a robotic defensive pattern, Rudan coached a collective intelligence into his players, making them capable of pressing a multitude of spontaneous variations in the opponent.

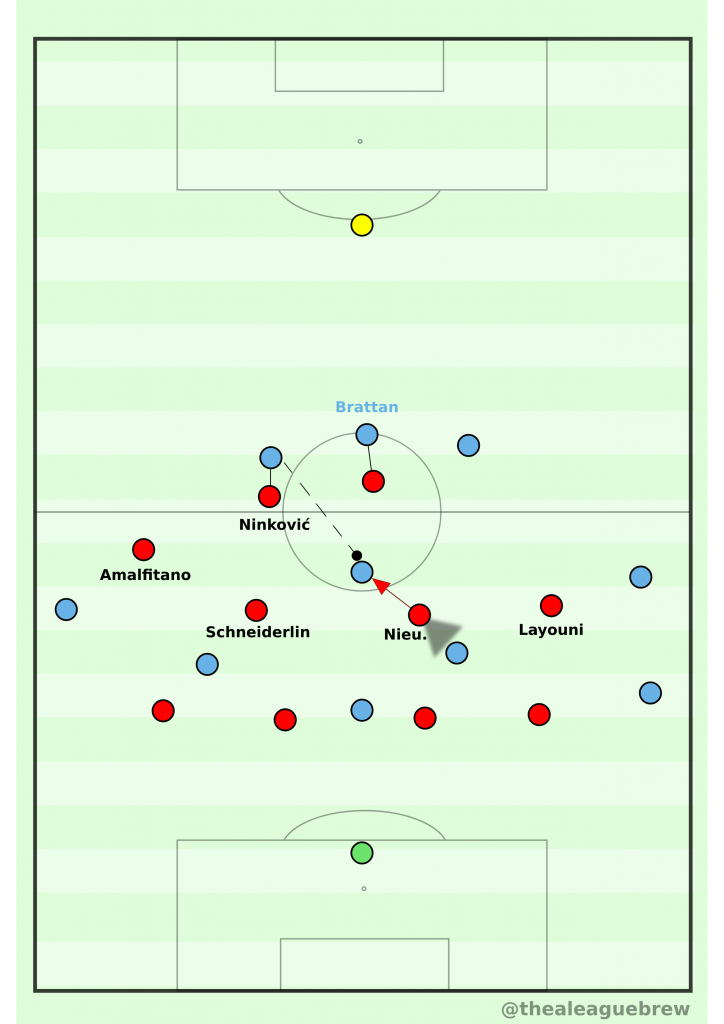

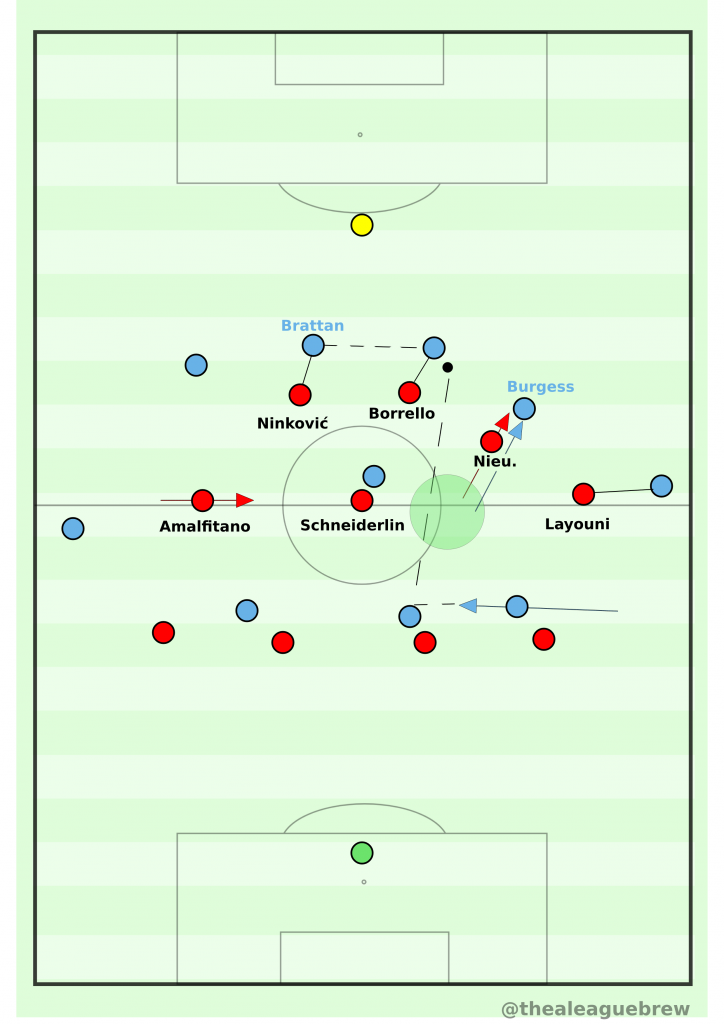

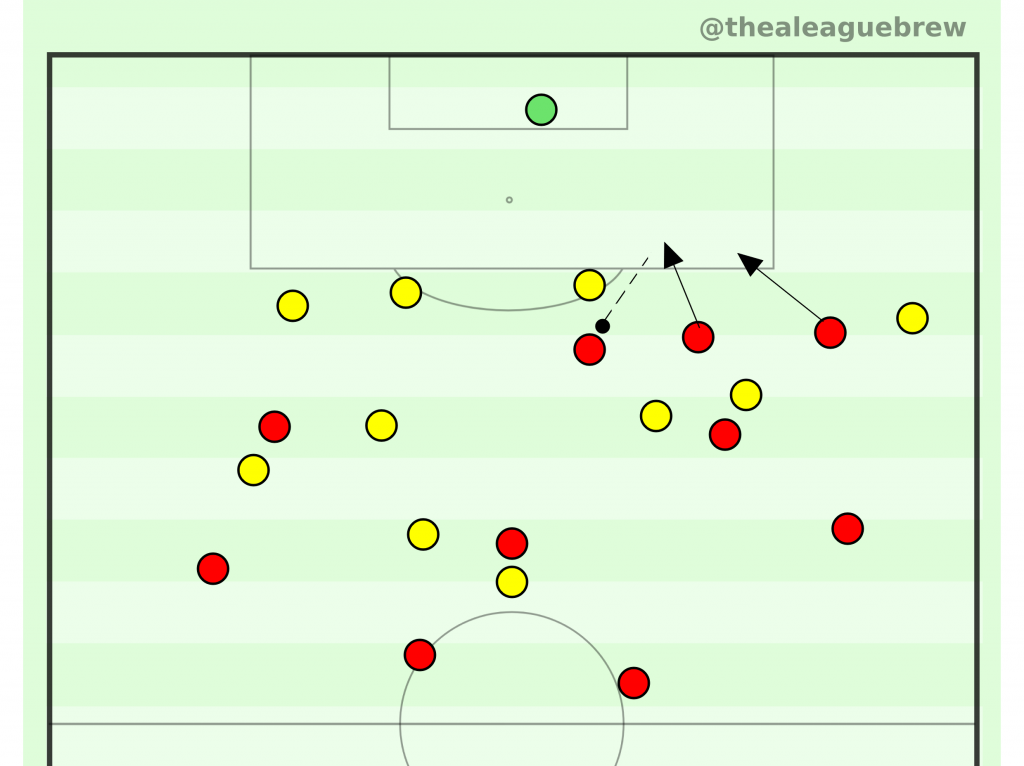

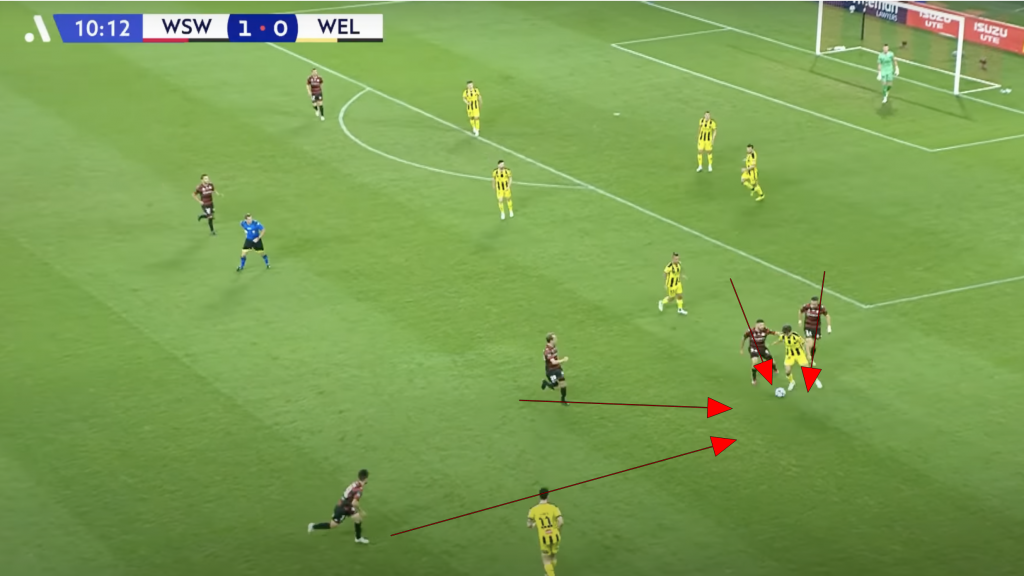

For example, in Diagram 3a, Wellington have circulated the ball excellently to the free CB, bypassing Ninkovic (ST) who is pinned to the pivot. Nieuwenhof (CM) recognises this and jumps out of the midfield-line to access the ball-carrying CB. Diagram 3b is exactly inverse, Ninkovic is pressing the ball-carrying CB, so Nieuwenhof jumps to close the pivot. Diagram 3c is another variation in which Ninkovic is pinned to the pivot, so Amalfitano (LM) jumps out to the ball-carrier.

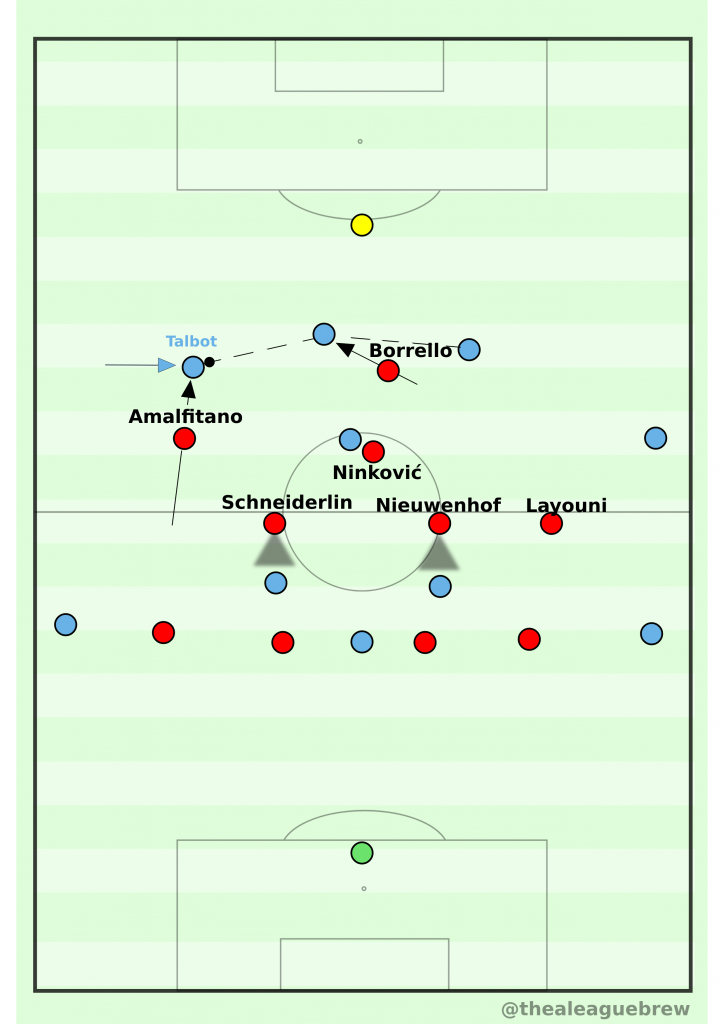

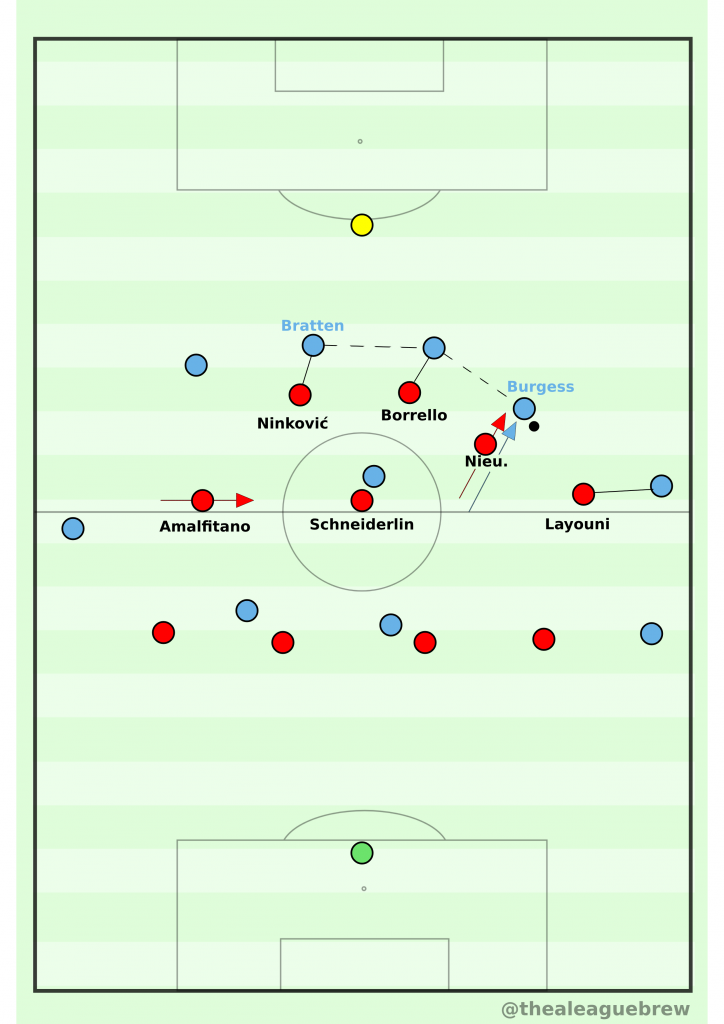

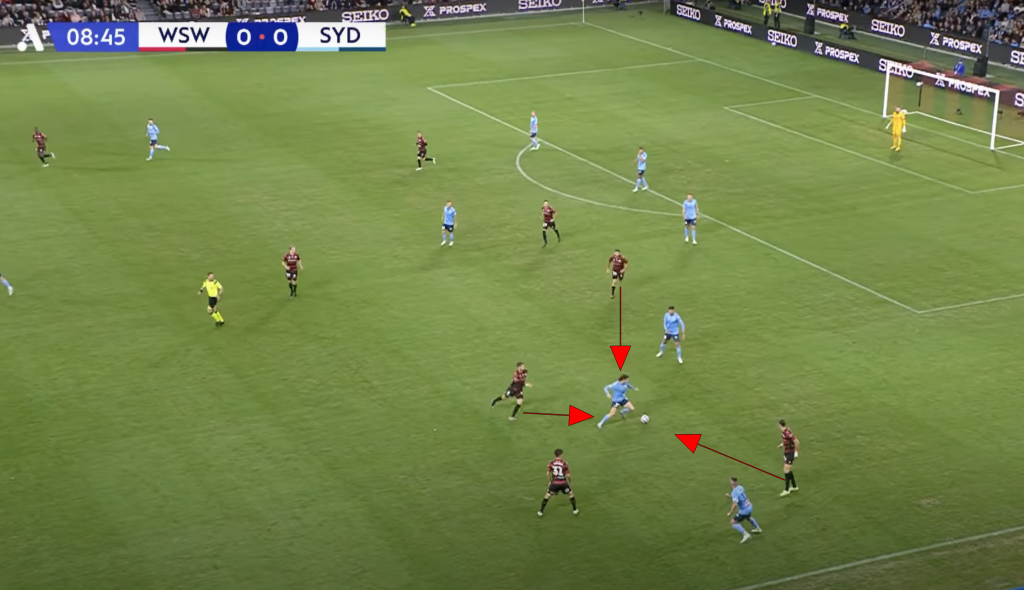

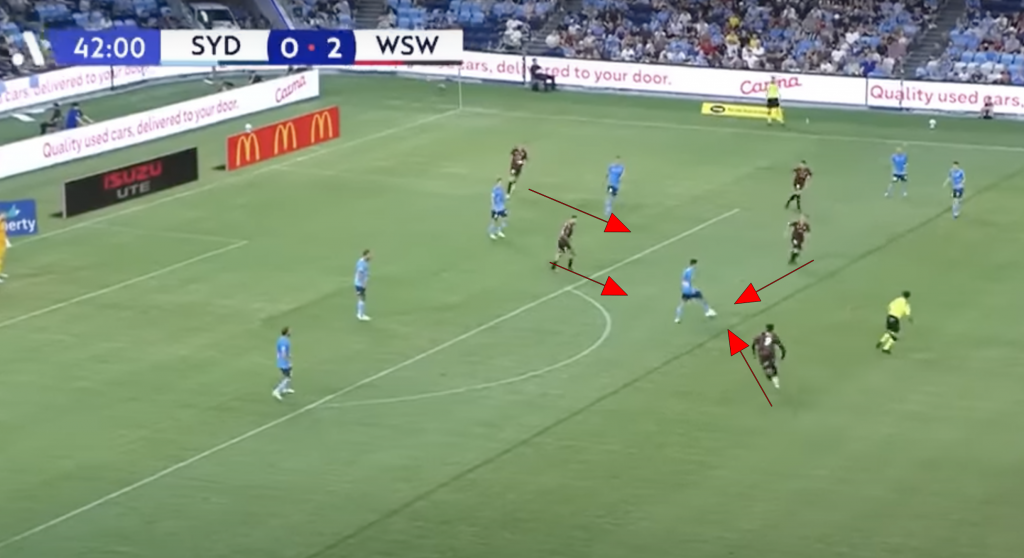

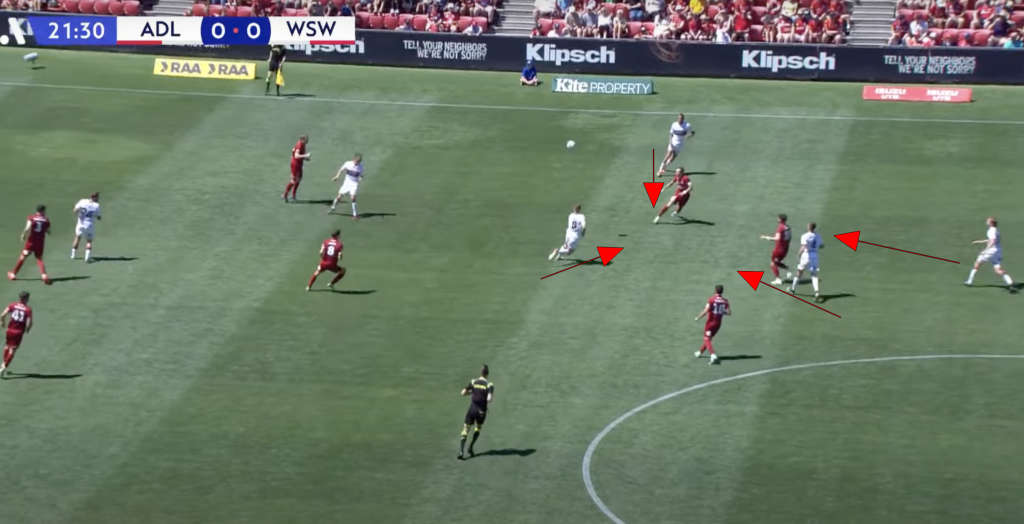

In Diagram 3d, Sydney FC drop both Brattan (CM) and Burgess (CAM) to the defensive line to aid ball-circulation. Ninkovic and Borrello (ST) close the center, Nieuwenhof jumps out to Burgess, while Schneiderlin and Amalfitano shift horizontally to cover the gaps in the midfield-line. In 3e, Borrello and Ninkovic are caught high against Adelaide’s split CBs, so Schneiderlin jumps out of the centre to press the free pivot leaving two opponents in his cover shadow.

It’s important to note the use of cover-shadows when jumping, and how they make it possible to effectively press even with numerical inferiority. When jumping out to a static ball carrier, the jumping defender catches the ball-carrier and the zone he has vacated in a vertical line (Diagram 3e – Schneiderlin). If the vacated zone has players in it, then they are blocked by the cover-shadow of the jumping defender, and cannot be immediately accessed by the team in possession. In Diagram 3e, the Wanderers’ pressing unit is outnumbered 8v6, however Schneiderlin’s jump catches 2 Adelaide players in his cover-shadow, making it possible for them to essentially press man-to-man despite true numerical inferiority. The risk of vacating a zone with 2 opposition midfielders in it for the reward of disrupting the opponents build-up through the centre, is such a great example of what the Wanderers were trying to achieve and what set them apart defensively from the rest of the league this season.

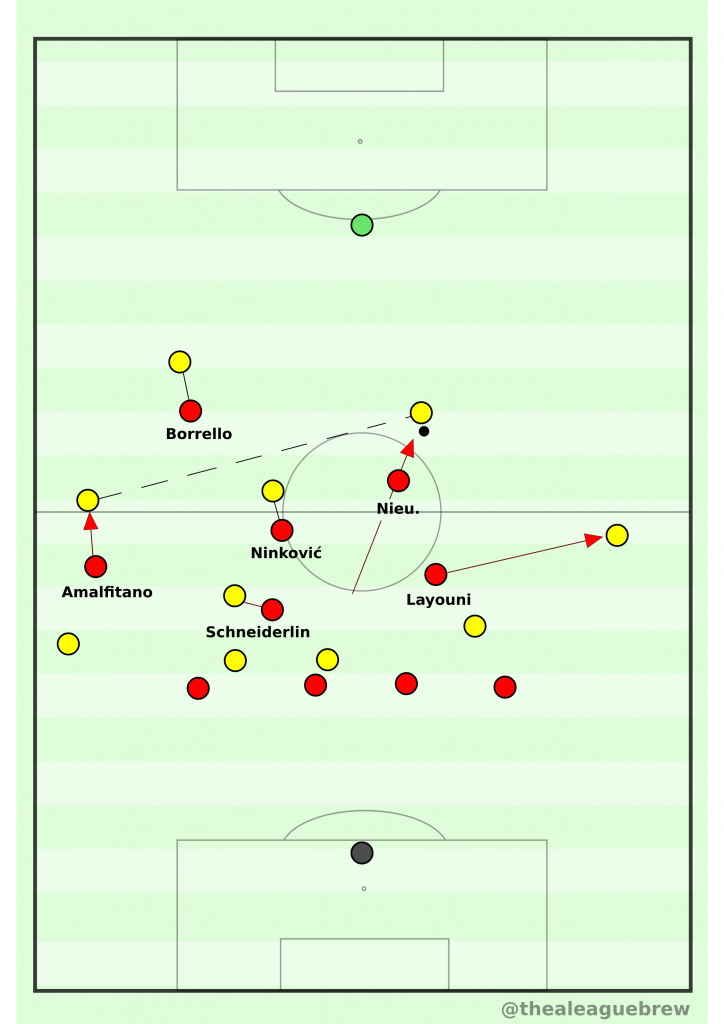

However, these defensive jumps that make the Wanderers effective at applying pressure can ultimately be a weakness if manipulated by the opponent. It’s possible to pull the Wanderers’ CMs out of the centre with false movements, as they have a strong attraction to players vacating their zone. This could most easily be executed against Nieuwenhof, who is by far the more active man-to-man presser of the two CMs. Below I’ve provided one example of how this might be accomplished.

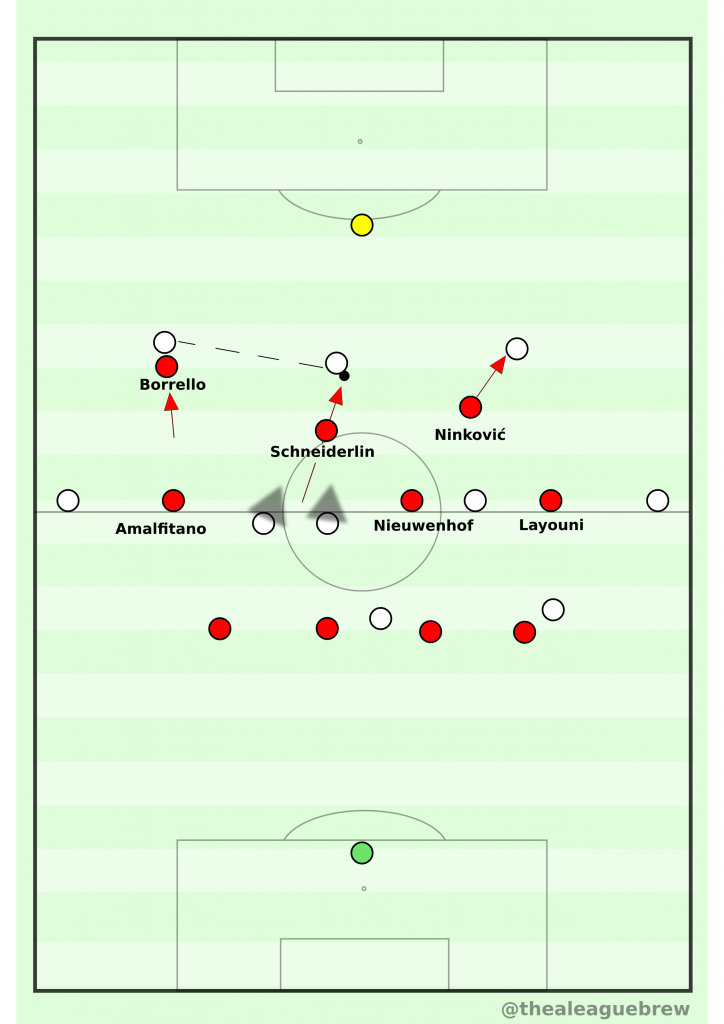

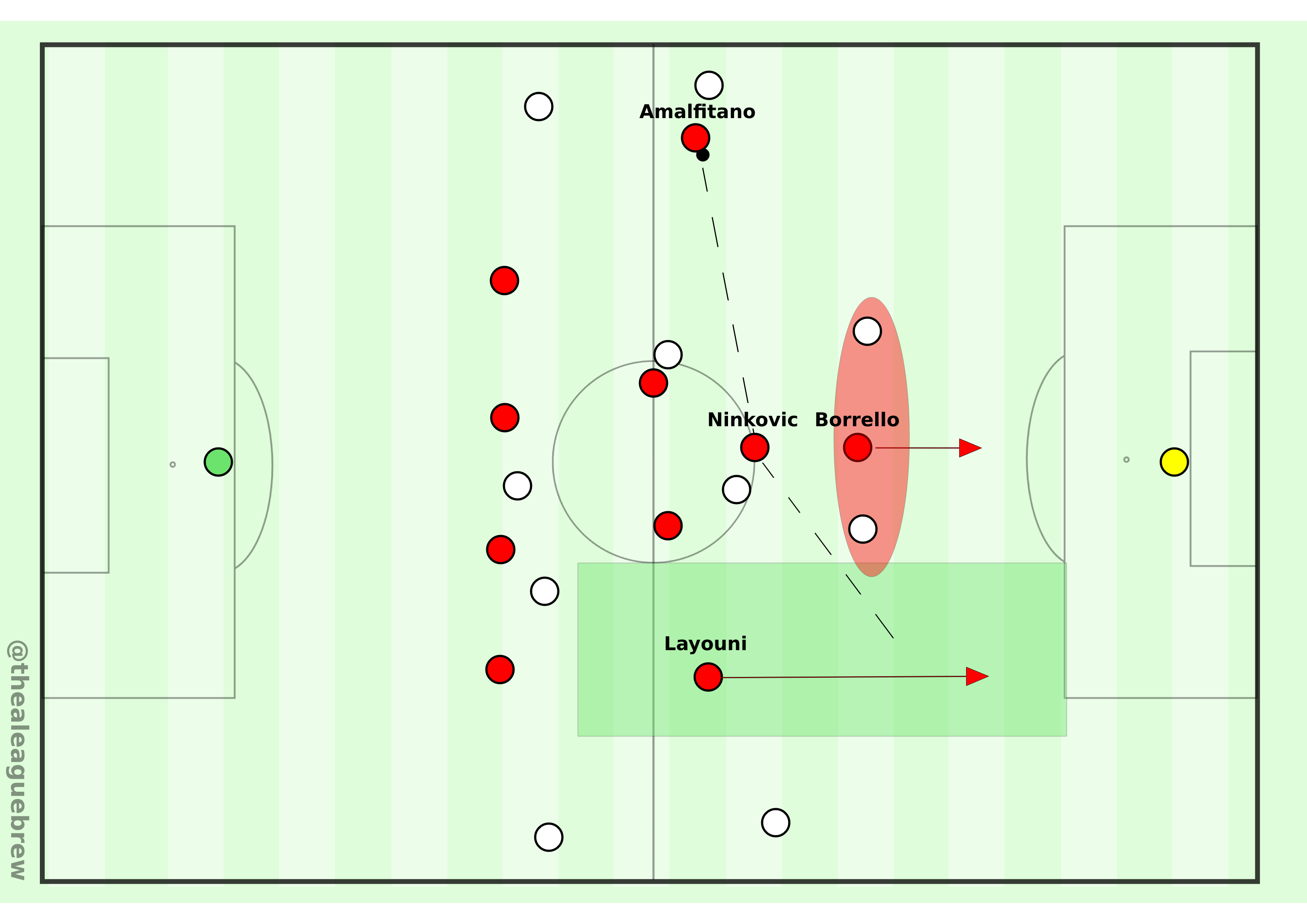

Let’s say we recreate Burgess’ movement earlier from Diagram 3d, but this time rather than receiving the ball Burgess is essentially a decoy run pulling Nieuwenhof out of position, and opening a useful passing lane through the centre (Diagram 4). By doing this we have sacrificed one of our midfield players in exchange for access to the Wanderers’ defensive line. By inverting a wide offensive player to support the recipient of the vertical pass, it’s possible to attack the CBs directly. Decoys of this nature were seldom seen however. In reality, Burgess lost the ball under significant pressure from Nieuwenhof, and the Wanderers attacked in transition.

Defence is the Best Form of Attack?

Rest-Attack

Broadly speaking, Rest-Attack describes the part of a defensive structure that prepares a team for the attacking phase. Here we will examine how the Wanderers’ medium-block defensive structure helped them prepare lethal counter-attacks in transition. In Spielverlagerung’s piece on Rest-Attacks, Judah Davies expertly defines the main counter-attacking roles as;

- Connector: a player who is centrally oriented, receives the ball quickly between the lines. The player is resistant to counter-pressure with technical dribbling, and combination-play. Looks to play passes into space for Wide Receivers (most effective when switching play to the far side).

- Wide Receiver/Carrier: utilises the space on the outside of the defensive line. Attacks this outside channel with speed to give momentum and progress to the transition.

- Binder: narrows the defensive line by positioning in between defenders or on their blind side, creating space on the outside for wide receivers. If a defender steps out to pressure the connector or wide receiver too early, he becomes available for through passes. Important role in finishing the counter-attack from cut backs, rebounds, and tap in opportunities.

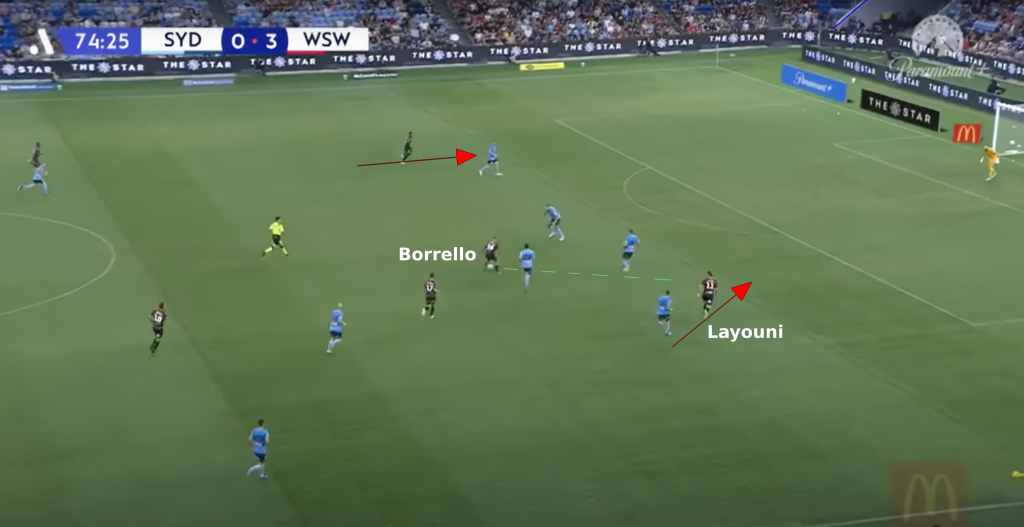

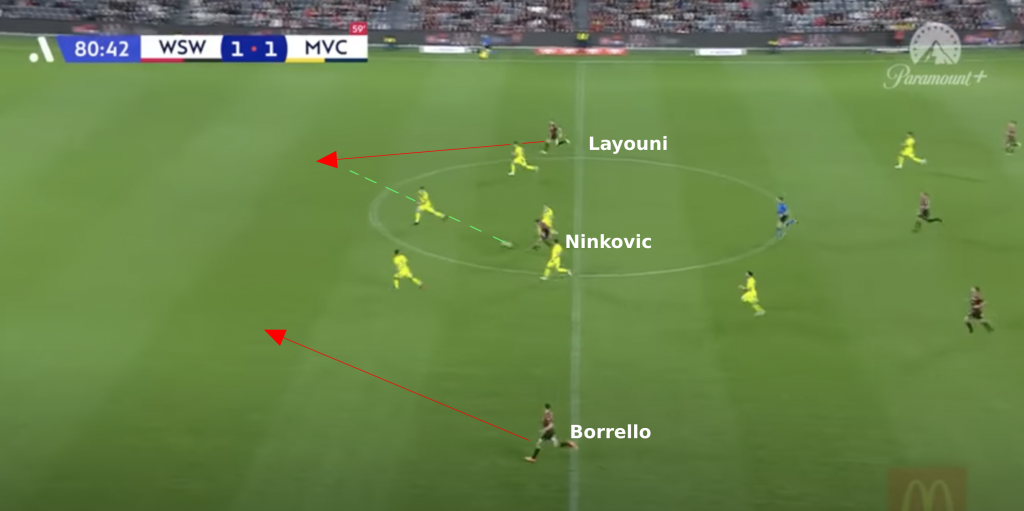

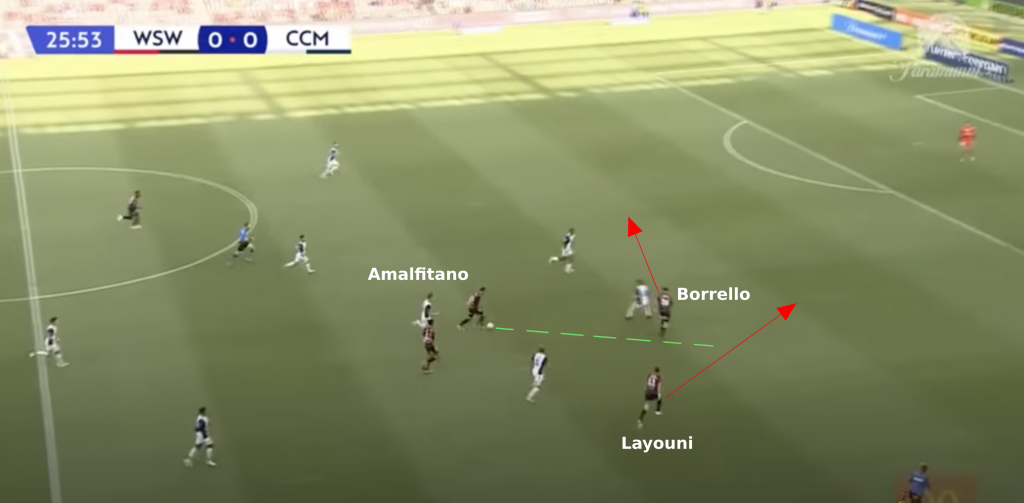

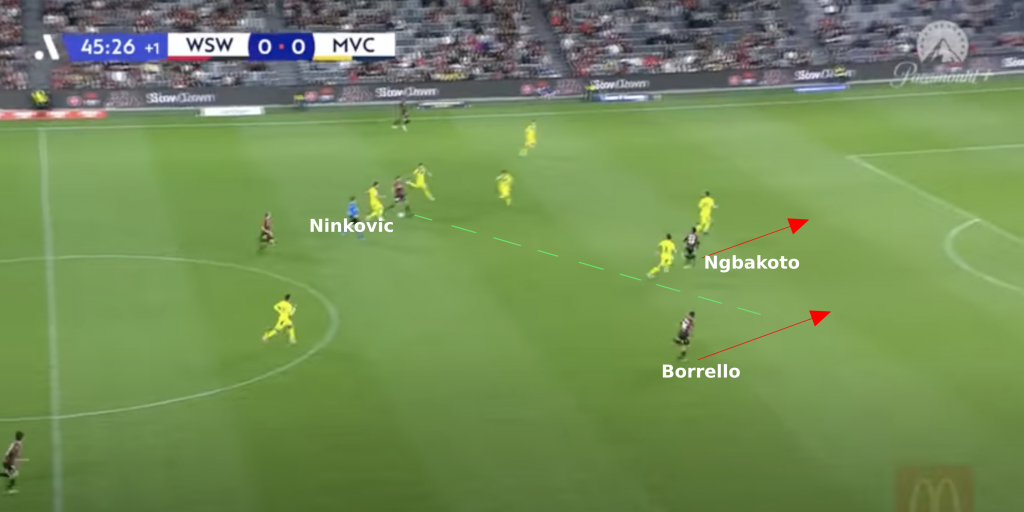

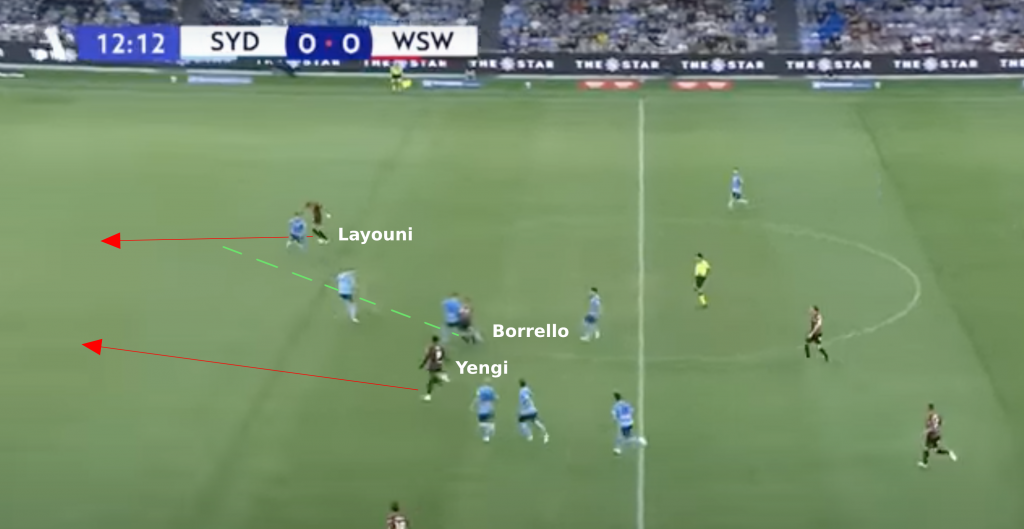

It’s clear that the Wanderers possessed individuals with the natural skill-sets to fulfill these roles; for example, technical Connectors in Ninkovic and Amalfitano, and pacy Wide Receivers in Layouni and Yengi. But the cherry up top is Western Sydney’s quintessential Binder, Brandon Borrello. His suitability for counter-attacking football is exemplified by 13 goals and 5 assists in 26 games, in which he demonstrated the technical, physical and tactical attributes to excel in all 3 counter-attacking roles.

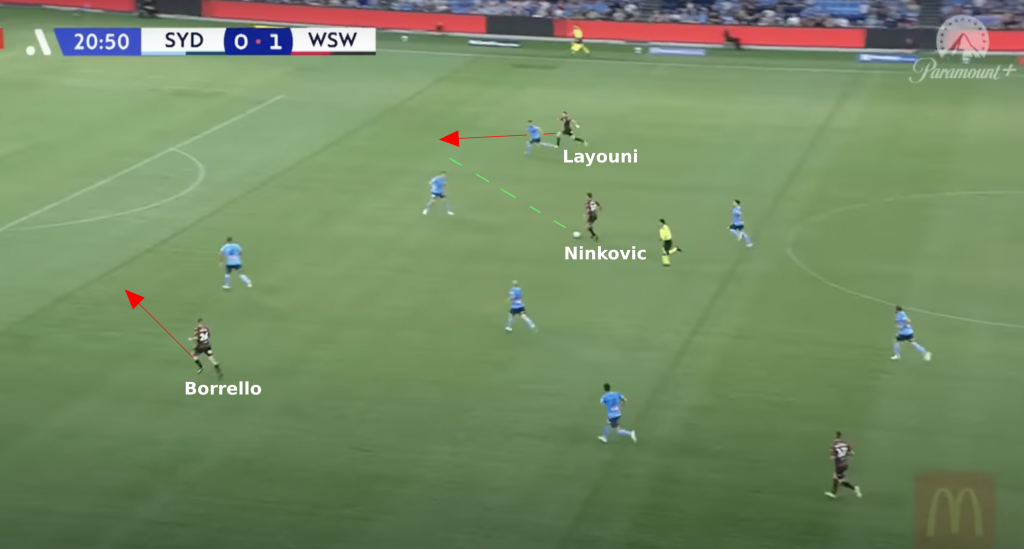

The Wanderers’ medium-block was deliberately organised to accentuate these natural roles in counter-attacking transition moments (Diagram 5). Ninkovic’s task to man-mark the pivot means he is already perfectly situated between the lines to act as a Connector upon transition (Images 2, 3 & 5 below). Layouni staying narrow when the ball is on the far side, so he can more easily attack the half-spaces on the outside of the defensive-line as a Wide-Receiver (Images 1, 2, 3, 4, & 6). Borrello constantly pressing the CBs so that in transition he is well positioned to manipulate them with his movements as a Binder, creating space for the Wide-Receiver, and arriving into the box to finish the play off (2, 3, & 4). As discussed, Borrello can drop to become an additional Connector between the lines (1 & 6), or take up the role as Wide-Receiver (5).

Counter-pressing

Counter-pressing is the action of applying pressure during transition from offence to defence, and under Rudan the Wanderers have profited greatly from the use of this tactic. When done successfully, the Wanderers can recover possession immediately after losing the ball, without having to drop deep into their medium-block structure. This gives them the advantage of attacking in an already advanced position, against an unorganised opponent.

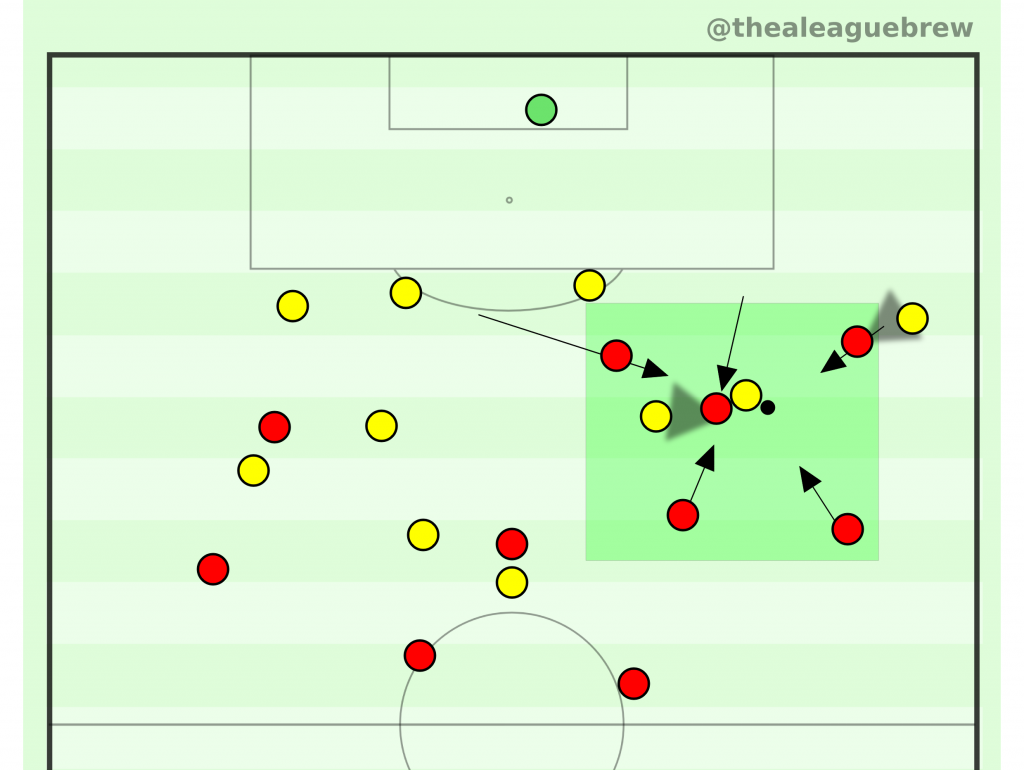

As can be seen in Diagram 6a, the Wanderers use a ball-oriented variation of counter-pressing, in which the team converges directly onto the ball-carrier in an attempt to block nearby passing options with cover shadows, force errors, and support attacking combination play once the ball has been won successfully.

There are a few key objectives that the Wanderers execute exceptionally well with respect to their ball-oriented counter-press. Firstly and most simply, they only initiate counter-pressure if a teammate can make an immediate impact on the ball-carrier, so that longer passes out of pressure are non-viable. Even if the opponent clears the ball out of play, the ball-oriented counter-press has not been a complete success. This is because the primary objective of ball-oriented counter-pressure, as opposed to man-oriented or passing-lane oriented variations, is that the team in question wants to engage-in and win duels with the opponent. Nieuwenhof, Schneiderlin, Borrello, Layouni, Ninkovic and Amalfitano are all players who are comfortable in engaging in combative duels.

Secondly, the Wanderers create an overload of players within the counter-pressing zone, whilst still maintaining an even spread across it. This is demonstrated in diagram 6a above, in which the Wanderers have a 5v3 overload within the shaded green zone, while pressing from five different directions to maximise spatial coverage.

Thirdly, the centre of the pitch must be cut-off from the ball-carrier. This is why, as can be seen in the images below, the majority of the Wanders’ counter-pressing actions occur within the wing-space, so that pressure can be applied from the centre toward the touchline.

Finally and perhaps most importantly, the Wanderers are pro-active. From a cognitive and positional standpoint, all players are prepared to counter-press even before they’ve lost the ball. Most impressive is the reaction time required for players in the highest line of attack (Borrello & Layouni in 1, 3 & 4 below) to engage in backwards pressing, a quality that is scarcely seen in the A-League. This is no doubt the result of hours of Rudan’s coaching on the training ground, while the clever recruitment of disciplined and high work-rate players is also a key component.

Conclusion

The Western Sydney Wanderers should be celebrated for achieving a level of defensive organisation that is seldom seen in the A-League Men’s competition. Mark Rudan coached a collective intelligence into his squad, who were capable of fluidly pressing spontaneous variations in the opponents build-up structure. He had the courage to promote aggressive and risky pressing patterns, that ultimately became one of their biggest attacking strengths, as the team profited in transition moments.