Melbourne City and the Central Coast Mariners competed in the championship-deciding match of the 2022/23 A-League Men’s season. From a footballing standpoint, with the drama of the location aside, the fixture promised to be one of the most intriguing A-League Grand Finals in years. On one side a purpose built, high-performance machine backed by the global conglomerate City Group, who were appearing in their 4th Grand Final in as many years; up against a locally oriented, community club on a shoestring budget who under the guidance of rising coach Nick Montgomery, achieved their best league finish in 10 years. On the pitch, the juxtapositions only continued. This analysis will discuss Montgomery’s industrious pressing pattern, MCY’s inability to capitalise on weaknesses in the Mariner’s low-block, and CCM’s aggressive verticalization and wing-play which ultimately won them the match.

Mariners Disrupt City Build-Up With Industrious Man-to-Man High-Press

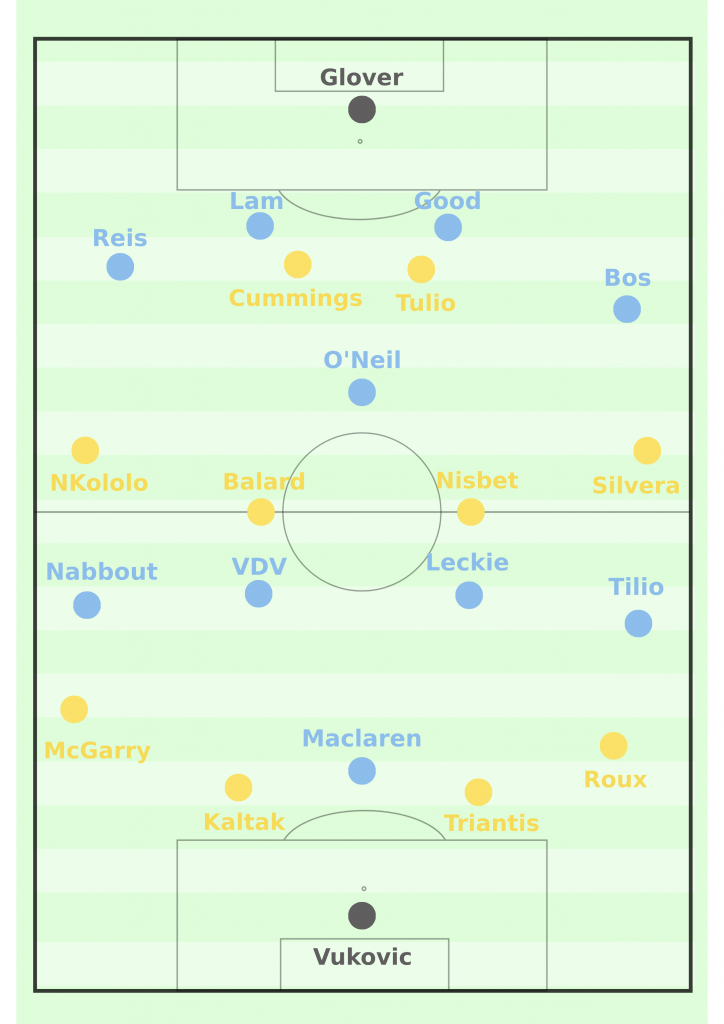

Up against the league’s most prolific side in positional attacks, Montgomery set the Mariners up to disrupt City’s possession early in the build-up phase using an aggressive man-to-man press, as he had done in the two sides’ previous A-League encounter back in April. Although this system leaves the Mariners susceptible to dismarking in midfield and direct attacks in behind their high-defensive line, these risks have largely been mitigated this season by the presence of Brian Kaltak, with the centre-back comfortable stepping forward to break-up midfield overloads and unmatched for pace when tracking runners in behind.

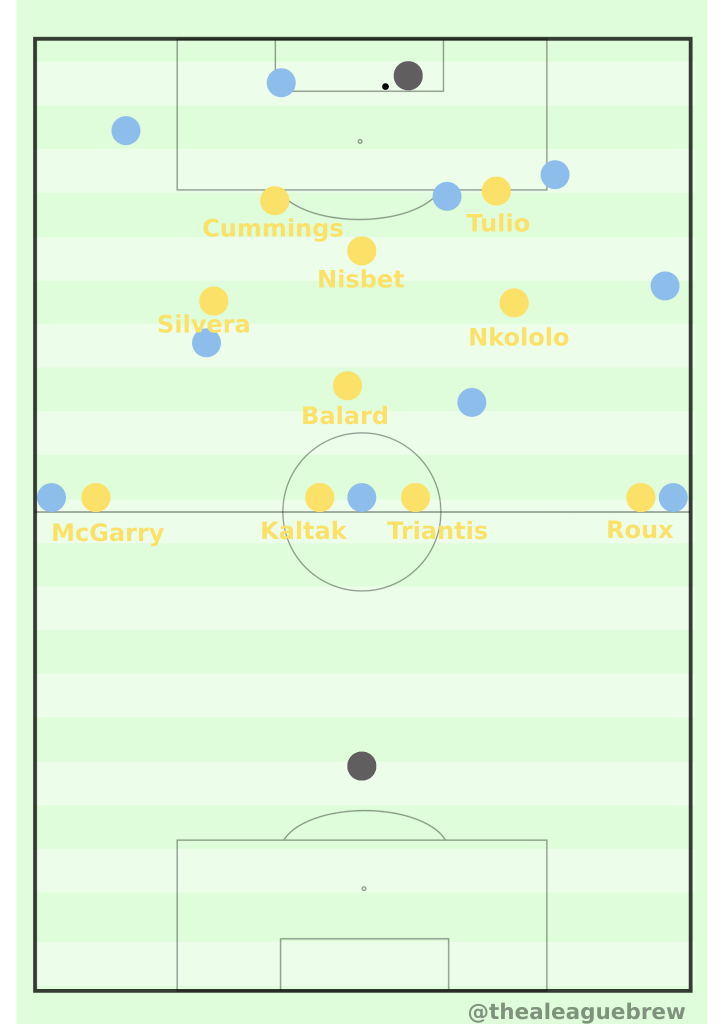

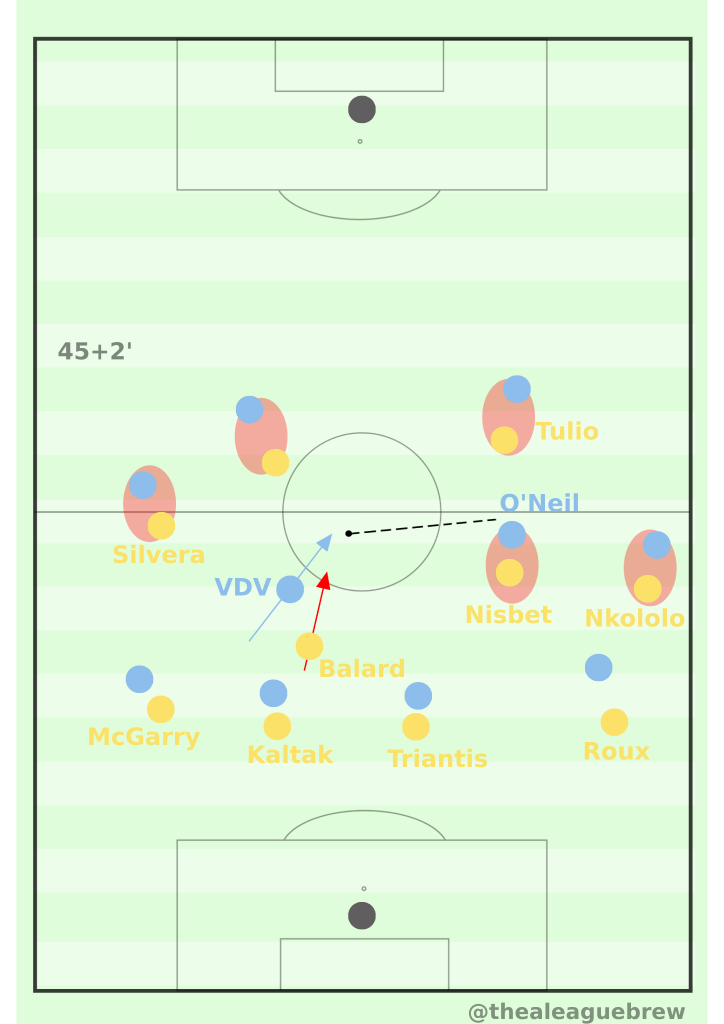

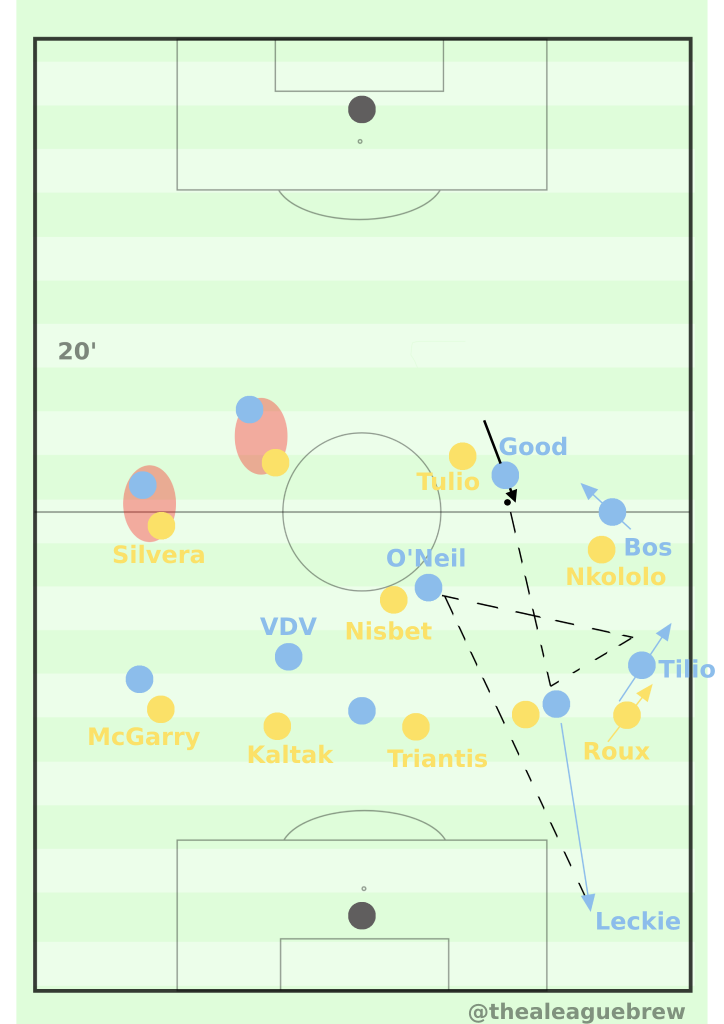

As City set-up to build-up from the back, the Mariners shifted out of a 4-4-2 into a narrow 4-1-2-1-2 zonal marking system. One of the CMs (usually Nisbet) pushed higher up the pitch to gain access to City’s lone #6, O’Neil, while the two wide-midfielders Silvera and Nkololo tucked inside to zonally cover the half-spaces either side of the remaining CM (usually Balard). The initial scope was to allow City the perception that they had sufficient time and space to build-up. However, as the ball travelled to either of the two CB’s the Mariner’s man-to-man high-press was triggered (Diagram 1b). The ball-side attacker immediately closed down the CB, who was forced to progress the ball wide to his fullback partner. By the time the fullback received the ball he was already under significant pressure from the Mariners’ ball-side wide-midfielder (Silvera) who had made an industrious sprint out to the wing to gain access. As this occured, the remaining Mariner’s CM (Balard) and ball-far WM (Nkololo) translated horizontally to access the two City #10s. Across both fixtures, the Mariners successfully achieved this in both dead ball (Diagram 1) and open play scenarios (Diagram 2).

Despite having previous experience with this exact same Mariners man-to-man pressing pattern back in April, City rarely executed planned positional rotations, third man passing combinations, or press-resistant ball carries to counteract it during the first half. They did occasionally sacrifice Berisha (van der Venne after his 22’ substitution) out of the offensive line, rotating into a double pivot with O’Neil (Diagram 2). This additional passing option in the centre was not accounted for by the Mariners’ pressing structure, and the resulting 3v2 made forward progression of the ball possible. However, it took City far too long to implement this tactic for it to have any real impact on the momentum of the first half.

Lack of City End Product Despite Issues in the Mariners’ Low-Block

The Mariners were always going to have issues defending deep against the best attacking outfit in the country. Following the half-time break, City began to combine more effectively against the high-press, and created a number of promising positional-attacks.

When the high-press was breeched, Montgomery had the Mariners drop deep to defend in a 4-4-2 ball-oriented zonal block, with two banks of four shifting together horizontally and vertically in order to minimise space between the lines. This system put significant defensive responsiblity on the less defensively inclined wide-midfielders Nkololo and Silvera, who were constantly re-positioning themselves based on the simultaneous movements of their teammates, the ball, and mutliple opposition players rotating through their zone.

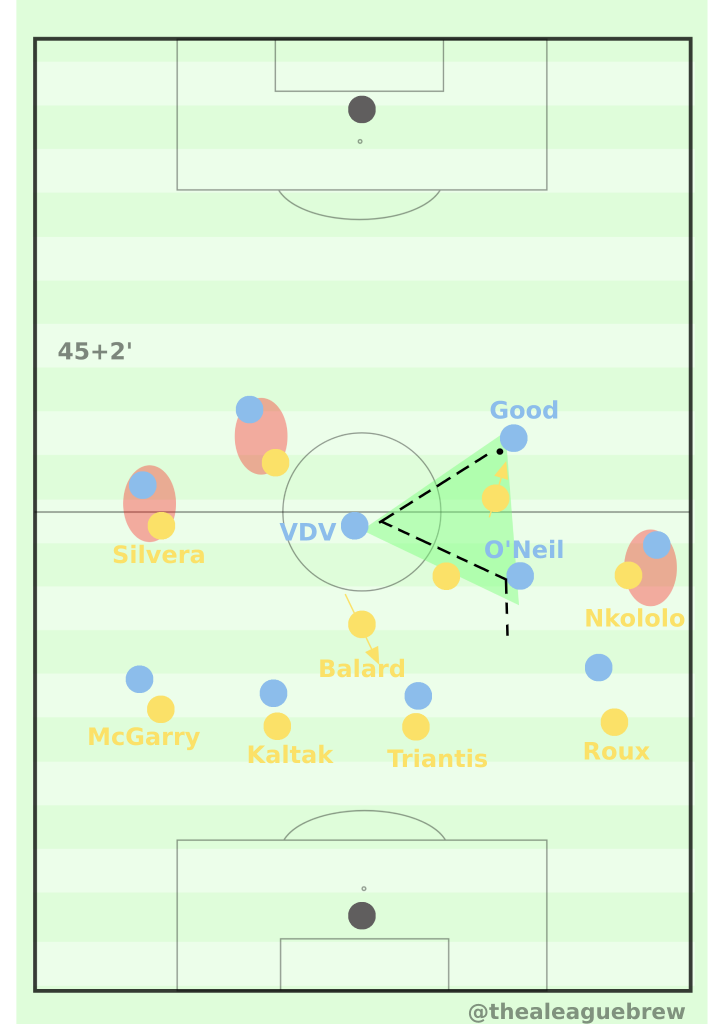

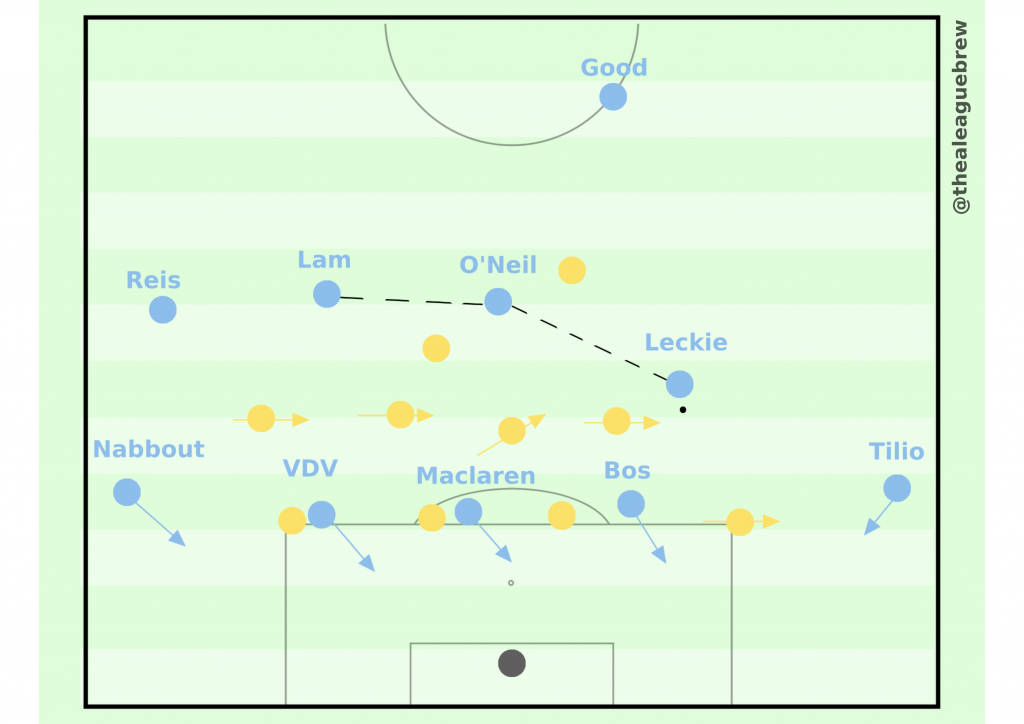

A hallmark of Melbourne City’s success over the years has been their ability to stretch and unlock compact, defensive low-blocks by occupying positions on both wings, in both half-spaces, and through the centre, while circulating the ball between these zones patiently. Under Rado Vidosic, they have continued to add complexity to their attack with dynamic position occupation (Diagram 4), a system in which players fluidly leave their natural positions to explore free positions in the formation, knowing that their previous position will then become occupied by someone else. Of course not every player is permitted equal fluidity, for example Maclaren’s position is more fixed in comparison to his teammates’ in order to centrally pin the two opposing CBs to the centre.

Dynamic position occupation allows City to achieve key objectives when executing positional-attacks, the first being to destabilise their opponents’ low-block. This is ultimately how City’s first goal arrived. A dynamic run forward from CB Curtis Good into the wing asks questions of Nkololo defensively, and he is swiftly played around with a simple 1,2 combination. Triantis then vacates his pinned position at CB to close down Good, leaving Maclaren completely unmarked in the half-space and able to cut the ball back for van der Veen to finish from the centre.

between the defenders.

Another of City’s key objectives when executing positional-attacks is for runners to vertically penetrate the spaces in between the opponents’ stretched back line for either one of the following; slipped passses into the half-spaces for cutbacks, inswinging crosses from the half-spaces, early crosses from the wings, or lofted passes in behind the defensive line from the centre. As can be seen in Diagram 5, teams defending in a back four give City five channels through which they can make penetrating runs, and they are often capable of attacking all five channels simultaneously. City found themselves in this situation multiple times throughout Saturday’s Grand Final, however were unable to capitalise on them mostly due to uncharacteristically poor technical execution at the final pass, dribble, or first touch.

Aggressive Verticalisation and Wing-Play Win the Match for the Mariners

If Melbourne City are the A-League’s experts at orchestrating complex positional-attacks through patient horizontal ball-circulation, then the Mariners juxtaposed that perfectly with lightning fast counter-attacking football and wing-play.

In many ways it was the perfect storm. As an inherent consequence of City’s dynamic position occupation, they were left exposed at the back and vulnerable to counter-attacks when possession was lost, while their Grand Final opponents were purpose built for counter-attacking football. Montgomery courageously went with a 4 man midfield for the majority of the Grand Final, leaving Cummings and Tulio as outlets during transition moments. This decision gave the players the capacity to fly through the middle-third in transition, with aggressive and sometimes risky vertical passes into the two frontmen. As the Mariners were rarely countering with numerical superiority, they looked to play out to the wings quickly where the pace and 1v1 ability of Silveira and Nkololo could be utilised.

Although City made a number of regrettable errors leading up to the goals (Bos and Good both closing down Tulio in the build up to Cummings’ opener, the unforgivable lapses in concentration during dead-ball situations for the second and fourth goals, and Reis’ poor clearance for the third), it should be said that the Mariners earned their chances through quick, clever, and courageous vertical play.

Conclusion

It was a Grand Final that will go down in A-League history for the emphatic 6-1 score line. Poetic justice for the triumphant underdogs was achieved by the execution of an aggressive tactical game-plan, of which Nick Montgomery, his team, and the wider Australian football community should be immensely proud.

Brilliant analysis. Great piece of writing and thoughtful disection of a piece of A-league history.

Valuable piece of content with a level of analysis that is rare in the current A-L media landscape.